The history of the modern American nation is often presented through a Protestant narrative that denies recognition of the role of other groups in the establishment of the modern United States. This narrative portrays American history as a war between Protestants, Catholics, whites, and Indians, neglecting the fact that these groups themselves were masters of slaves on sugar plantations and also enslaved Africans in coordination with whites. However, the most serious aspect of all this is that the majority of these slaves were Muslims, deprived of their freedom and the freedom to practice their rituals. In some cases, they were forcibly converted and deprived of any affiliation with Islam or Arab identity. Many of them were educated and doctors and princes in their home countries.

The following article tells the story of this transformation and erasure through three stories of prominent Muslim figures whose lives were turned upside down overnight, forced into things they were not accustomed to at the height of European slavery.

The first words that crossed between Europeans and the inhabitants of America (as biased and confusing as it may seem) came from the language of Islam. Christopher Columbus hoped to sail to Asia and prepared to communicate with its magnificent population by resorting to one of the greatest languages in Eurasian trade. So when Columbus’s translator, a Sephardic Andalusian, addressed the Taino Caribs, he did so using the Arabic language. Not only was the language of Islam used, but the religion itself likely reached America in 1492, 20 years before Martin Luther nailed his thesis to the church door, initiating the Protestant Reformation.

The Moors

The Moors – Africans and Arabs – conquered most of the Iberian Peninsula in 711 AD, establishing an Islamic culture that lasted for about eight centuries. By the beginning of 1492, the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella concluded the Reconquista wars, with the defeat of the last Muslim kingdom, the Kingdom of Granada. By the end of that century, the Inquisition courts, which began a century earlier, had forced around 300,000 to 800,000 Muslims (and at least 70,000 Jews) to convert to Christianity. Spanish Catholics usually suspected that those Moriscos or converts to Christianity were secretly practising Islam (or Judaism), so the Inquisition courts pursued and tried them. Some of these, almost certainly, had sailed with Columbus’s crew, carrying Islam in their minds and hearts.

Eight centuries of Islamic rule in Spain left a deep cultural legacy, evident in clear and sometimes surprising ways during the Spanish conquest of America. Bernal Diaz del Castillo, the chronicler of Hernan Cortes’s conquest of Central America, admired the costumes of the American dancers and wrote, “They were beautifully dressed in their own style and there was nothing like the Moorish women.”

The Spanish began to use the term “Mezquita” (mosque) to refer to the religious sites of the indigenous Americans. In his travels through the Anahuac (now known as Texas and Mexico), Cortes reported seeing over 400 mosques.

Islam served as a kind of detailed map or algorithm for the Spanish in the “New World.” Encountering new people and things with all the urgency, the Spanish turned to Islam to try to understand what they saw and what was happening. Even the name “California” may have Arabic origins. The Spanish launched the name, in 1535, by drawing it from “The Deeds of Esplandian,” published in 1510, a romantic novel full of “conquistadors.” The novel tells of a rich island – California – ruled by the Amazons and their queen, Calafia. The novel was published in Seville, the city that spent four centuries as part of the Umayyad Caliphate (Calafia, California).

Throughout half the globe, wherever the new lands were trodden or the indigenous people encountered, explorers recited the “Requirement” – a finely crafted legal declaration. Essentially, it was an announcement of a new societal order: offering the indigenous Americans the opportunity to convert to Christianity and submit to Spanish rule, or else bear responsibility for all the “deaths and losses” incurred. The official and public announcement of the intention to conquer, including an offer to non-believers to convert to believers, is the first condition of jihad in Islam. After centuries of wars with Muslims, the Spanish adopted this practice, imbuing it with a Christian flavor, calling it the “Requirement,” then bringing it to America. Perhaps the Spanish Christianists believed Islam to be a sin, or demonized it, but they also knew it well. Even if they found it strange, it must have been a familiar kind of strangeness.

By 1503, Muslims themselves, from West Africa, had set foot in the “New World.” In that year, the royal governor of Central America wrote to Isabella asking her to reduce the numbers imported. They were, as he noted, “a scandal to the Indians.” They were, in his words, often “running away from their masters.” And on New Year’s Day of 1522, the first slave revolt in the New World erupted, when 20 slaves from Central America rebelled on sugar plantations and began killing Spaniards. The rebels, as the governor noted, were mostly Wolof, a Senegambian people who had begun embracing Islam since the 11th century. Muslims were more likely than others to be literate: a skill not often seen as an advantage by farm owners. In the five decades following the slave revolt in Central America, Spain issued five decrees banning the importation of Muslim slaves.

Thus, Muslims had set foot in America over a century before the Virginia Company established the Jamestown colony in 1607. And over a century before the Puritans established the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. Muslims lived in America not just before the Protestants but before Protestantism itself. After Catholicism, Islam was the second most widespread monotheistic religion on the continents.

The prevailing misunderstanding, even among scholars, that Islam and Muslims are new additions to America tells us important things about how American history is written. Specifically, it illustrates how historians justified and generalized the emergence of the modern nation-state. One way to celebrate America was by reducing its diversity and scope – cosmopolitanism, or the diversity and coexistence among individuals – during the first 300 years of European presence in America.

The writing of American history was dominated by Puritan institutions. It may be far from accurate to claim, as historian (and Southerner) U.B. Phillips complained over a century ago, that Boston wrote the history of the United States, and wrote it largely wrongly. But concerning the history of religions in America, the consequences of the dominance of leading Puritan institutions in Boston (Harvard University) and New Haven (Yale University) were profound. This “Puritan impact” on the early American religious landscape (and the origins of the United States) leads to actual distortion: as if we were to surrender the political history of 20th-century Europe to the Trotskyists.

So let’s think of history as the depth and breadth of human experience, as it really happened. History makes the world, or the place and people, what they are. Conversely, let’s think of the past as those pieces and snippets of history chosen by a society from among societies to establish itself, and affirm its forms of governance, institutions, and prevailing ethics.

Forgetting the early Muslims in America is, then, more than a mystery. Its consequences have a direct impact on the essence of political belonging today. Nations are not mausoleums or boxes for preserving the dead and things. They are an organic membership, a living thing that, as it is being constructed, should constantly be reconstructed, or else it will weaken and die. The practical monopolization that Anglo-Protestantism carried out on the history of religion in the United States obscured half a millennium of Muslim presence in America and made it difficult to grasp clear answers to important questions about who belongs, who is American, by what standards, and for whom the decision is made.

What should “America” or “American” mean?

Through its “Early America, Expansive” program, Omohundro, the leading research institution in early American history, points to one possible answer: both “Early America” and “American” are large, vague terms, but not to the extent of being almost meaningless.

Historically, they can best be understood as a massive collision, a mingling and opening up of peoples and civilizations, (and animals and microbes) between Europe and Africa and between the peoples and societies of the Western Hemisphere, from the Greater Antilles to Canada, beginning in 1492. From 1492 until at least 1800, America, simply put, was defined as either Greater America or Early, Expansive America.

Muslims were part of Greater America from the start, including those parts that became known as the United States. In 1527, Mustafa al-Zamori, an Arab Muslim from the Moroccan coast, arrived in Florida as a slave in a Spanish expedition that was destroyed under Panfilo de Narvaez. Against all odds, al-Zamori survived and established a life for himself, traveling from the shores of the Gulf of Mexico to what is now the southwestern United States, as well as Central America. He struggled as a slave for the indigenous people before establishing himself as a respected physician.

In 1542, Cabeza de Vaca, one of the four survivors of Narvaez’s expedition, published his first European book, later known as “Adventures in the Unknown Interior of America,” which he dedicated to North America. De Vaca spoke of the disasters that befell the explorers and the eight years spent wandering through North and Central America. Referring to al-Zamori, he concluded: “He was the black man who addressed them all the time.”

These “theys” returned to the indigenous population, and al-Zamori’s proficiency with the languages of the indigenous inhabitants preserved their lives and, after some time, allowed them a degree of prosperity.

The Moroccan Mustafa al-Zamori saw more of the United States, its lands, and people than any of the country’s Founding Fathers – indeed, more than any group of them combined. Laila Lalami captures all this and more in her exquisite novel “The Moor’s Account,” published in 2014, tracing Zamori’s journey from his childhood in Morocco, to his enslavement in Spain, and then his mysterious end in the American Southwest. If there is anything to be said about being the best version of American pioneers or the spirit of horizon, or something of the echoic, tentative experience of adaptation and reinvention [of the self] that can stamp a nation or a people, it will be difficult to find someone who represents these matters better than Mustafa al-Zamori.

Between 1675 and 1700 AD, the beginnings of agrarian society in Chesapeake enabled local slaveholders to bring more than 6,000 Africans to Virginia and Maryland. This surge in trade led to a significant change in American life. In 1668 AD, the number of white servants in Chesapeake outnumbered black slaves by five to one. But by 1700 AD, the ratio reversed. Over the first four decades of the 18th century, more Africans came to Chesapeake. Between 1700 and 1710 AD, the growing agricultural wealth led to the importation of another 8,000 Africans. Then by the 1730s, at least an additional 2,000 slaves came to Chesapeake. American Chesapeake was transitioning from a society with slaves (like most societies in human history) to a society of slaves, which is stranger than usual. In a society of slaves, slavery is the pillar of economic life while the relationship of the slave to the master serves as a model for social relations, upon which the rest depend.

Among the first generations of Africans brought to North America, working in adjacent fields and sleeping under their owners’ roofs predominated. As historian Ira Berlin notes in his book “Many Thousands Gone,” published in 1998, they were largely driven by a strong desire to convert to Christianity, hoping to secure some social standing. In the case of West Africans brought in the late 17th and early 18th centuries to work as slaves in Virginia, Maryland, and the Carolinas, they came either from scattered parts of Africa or from the West Indian islands, compared to previous “Charter” generations. They were more likely to be Muslims and much less likely to be of mixed descent. Christian evangelists and farmers in the 18th century complained that the “generation of farmers” among the slaves showed little interest in Christianity. They criticized what they saw as some slaves practising “pagan rituals,” which allowed Islam, to some extent, to persist in the slave society of America.

Similarly, between 1719 and 1731 AD, the French benefited from the civil war in West Africa to enslave thousands, bringing 6,000 Africans to Louisiana. Most of them came from Futa Toro, a region near the Senegal River and now between what is currently Senegal and Mauritania. Islam entered Futa Toro in the 11th century. Since then, it has been known for its numerous scholars, jihadi armies, and religious governments, including the “Imamate of Futa Toro,” a religious government that existed between 1776 and 1861 AD. The African conflicts between the late 18th and early 19th centuries in the “Gold Coast” (now known as Ghana) and Hausa Land (which largely constitutes present-day Nigeria) had repercussions in America. In the former, the Ashanti managed to defeat the African Muslim alliance. In the latter, the jihadists eventually triumphed but lost many of their sons to the slave trade and the West.

Ayuba Suleiman Diallo is one of the most famous Muslims in 18th-century North America. He was a Fulani, a Muslim group from West Africa. At the beginning of the 16th century, European traders enslaved many Fulani and sent them to be sold in America. Diallo was born in Bondou, an area located in the Senegal and Gambia River basin, under an Islamic religious government. He was captured by a British slave trader in 1731 AD, and then sold to a slave owner in Maryland. An evangelical mission distinguished Diallo’s Arabic writing and offered him wine to test his Islam. Later, a British lawyer who wrote Diallo’s affidavit about his enslavement and transition to Maryland Anglicized his first name to “Job” and his second name to “Ben Solomon.” Thus, Ayuba Suleiman became “Job Ben Solomon.”

In this way, the experience of slavery and passage to America witnessed the Anglicization of many Arabic names, where Quranic names became familiar in the King James Bible. Musa became Moses, Ibrahim became Abraham, Ayub became Job, Dawud became David, Sulaiman became Solomon, and so on. Toni Morrison drew on the history of Islamic naming practices in America in her novel “Song of Solomon,” published in 1977. The title of the novel is derived from a folk song that hints at the history of the protagonist, “Milkman Dead,” and his family. The fourth line of the song begins: “Solomon and Rina, Bilali, Shalute / Yaruba, Medina, and Mamut.”

Solomon: Sulaiman Bilali: Bilal Shalute: Jalut Mamut: Muhammad These names came from African Muslims who were enslaved in Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky, the Carolinas, and other places in America. “Song of Solomon,” in other words, (and perhaps initially) was the song of Solomon.

Renaming slaves (sometimes with derogatory or mocking qualities) was an important tool for agricultural authorities, rarely overlooked. However, Arabic names throughout North America were preserved as part of the historical record. Court records in Louisiana from the 18th and 19th centuries show procedures related to individuals named Mansur, Shuman, Imad, Fatimah, Yassin, Musa, Bakri, Ma’mari, and others. Similarly, court records from the 19th century in Georgia detail legal proceedings involving Salim, Bilal, Fatimah, Isma’il, Aliq, Musa, and others.

Nupe Burton, a 20th-century sociologist, spent his life compiling ethnographic material on the cultural life of African Americans. In his book “Black Names in America: Origins and Usage,” Burton documents over 150 common Arabic names among those of African descent in the southern United States. Sometimes an individual could bear an Anglicized name or a “slave name” for official purposes, while the Arabic name prevailed in daily practice.

It’s difficult to ascertain the extent to which Arabic names associated with religious or continued identity practices persisted, but total discontinuation seems unlikely. For instance, an advertisement in a Georgia newspaper dating back to 1791 mentions a runaway slave named “Jeffrey… or Ibrahim.”

Considering the controlled naming practiced by slave owners, it’s likely that many who were called Jeffrey were actually “Ibrahim,” and many women named “Missy” were actually “Masumah,” and so forth.

Lorenzo Dow Turner, a mid-20th-century researcher in Gullah language (a creole language in the “Sea Islands” region of the southeastern United States), documented “about 150 names of Arabic origin” relatively common in the Sea Islands alone. These include Akbar, Amina, Hamid, and many other names. Mustafa was a popular name on farms in the early 19th century in the Carolinas. Arabic names don’t necessarily denote someone as Muslim, at least not in Morocco or the Levant, where Arabs are Christians and Jews as well. However, it was the spread of Islam that brought Arabic names to West Africa. Hence, these Africans or African Americans from Amina and Akbar, or at least their fathers or ancestors, were likely Muslims.

Out of fear, Spanish authorities attempted to ban Muslim slaves from their early American settlements. In the tightly knit and secure Anglo-American slave society of the 18th and 19th centuries, many plantation owners favored Muslims. In both cases, the same conclusion was drawn: Muslims were distinguished, wielded power, and exerted influence. One publication — “Practical Rules for the Management and Medical Treatment of Negro Slaves in the Sugar Colonies,” issued in 1813 and focusing on the West Indies — noted that Muslims were “excellent in caring for cattle and horses and for domestic service,” but “had few qualifications for rougher field work, and for this reason should never be employed.” The author also notes that “many of them converse in the Arabic language” on those farms.

Some slave owners in early 19th-century America themselves were Muslim slaves, teachers, or officers in the African army. Ibrahim Abdul Rahman, for instance, was a colonel in his father’s army, Ibrahim Shah of Syria, the ruling prince of Futa Jallon, now known as Guinea. In 1788, at the age of 26, Abdul Rahman was captured in war, sold by British traders, and then transported to America. Abdul Rahman spent about 40 years picking cotton in Natchez, Mississippi. His owner, Thomas Foster, called him “Prince.”

Abdul Rahman performed his prayers as a Muslim. When he met leaders of the American colonization movement, he informed them of his Muslim faith. However, Thomas Gallaudet, a prominent evangelical who studied at Yale University and was active in education, gave Abdul Rahman an Arabic copy of the Bible and asked him to pray with him. Later, in hopes of being able to return to Africa and obtain a meaningful position, Arthur Tappan, a prominent American philanthropist, pressured Abdul Rahman to become a Christian preacher and help him expand the profitable Tappan Brothers commercial empire to Africa.

The African Repository and Colonial Journal described how Abdul Rahman “would become the first pioneer of civilization to unenlightened Africa.” They saw him planting “the cross of the Redeemer over the summits of the lofty mountains in Kong!” This, in essence, is the way of the Puritanical influence. Firstly, Abdul Rahman was stripped of his religion and self-definition. Secondly, influential institutions in writing, record-keeping, publishing, and education (essential skills in transforming history into the past) began to distort it in their own way.

The details of Abdul Rahman’s story may be rare. Still, his experience as an American Muslim facing Anglo-Protestant hegemony intent on manufacturing a “Christian” nation is not unique. Islam, in part, evolved to accommodate the vast linguistic and cultural differences in Africa and Asia: Abdul Rahman spoke six languages. Evangelical Protestantism among Anglo-Americans, in contrast, is a relatively recent and narrow religion. It gained its footing in a limited area of the North Atlantic and had a dynamic relationship with both capitalism and nationalism. Its aim is not to transcend difference but to (as both Gallaudet and Tappan were trying to do with Abdul Rahman) impose homogeneity.

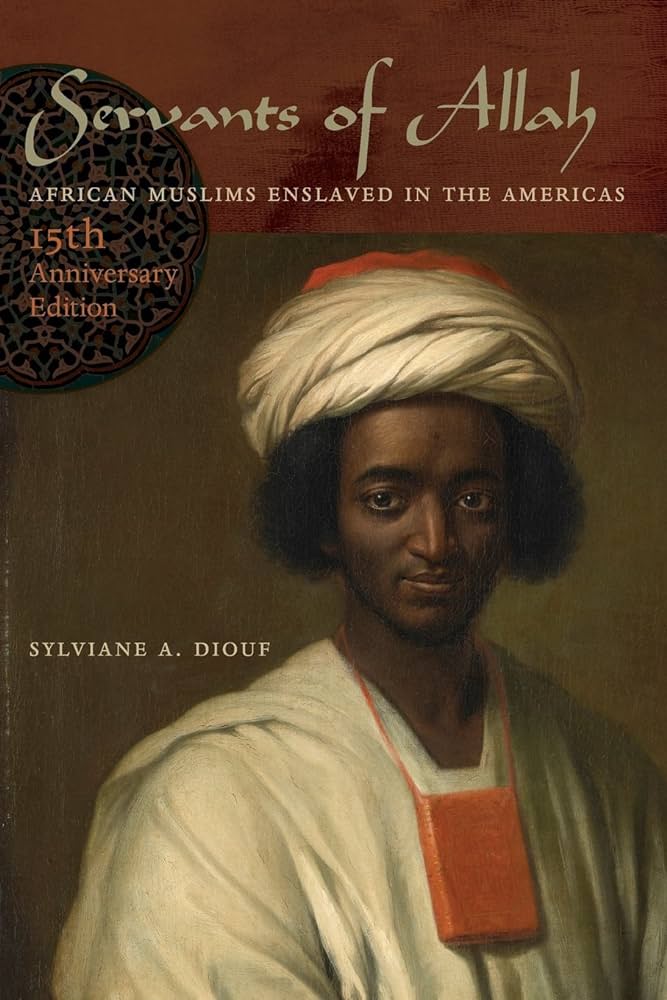

How many people shared Abdul Rahman’s experience at its basic levels? How many Muslims were there in America between, say, 1500 and 1900 AD? How many of them were in North America? Sylviane Diouf is an accomplished historian in this regard. In what could be considered a conservative estimate, Diouf writes in “Servants of Allah,” published in 1998:

“There were thousands of Muslims in America, and perhaps that is not all we can say about numbers and estimates.”

Of the ten million or more Africans enslaved and sent to the New World, over 80 per cent went to the Caribbean or Brazil. Nevertheless, the numbers of Muslims who came to early America were much greater than those of Puritans who arrived at the height of Puritanical colonization. The peak settlement period, between 1620 and 1640 AD, saw 21,000 Puritans come to North America. Perhaps 25% of these came as servants, and it is difficult, consequently, to assume they had Puritanical sentiments and opinions. By 1760 AD, New England was home, at best estimate, to 70,000 church members (Puritans) in New England.

Despite these relatively small numbers, the Puritans succeeded in becoming a community of educators and educators for the nation. But in some respects, New England also lost out during the rise of the United States of America. It reached the peak of its economic and political influence in the 18th century. Despite its prominent role in the independence of the United States, it never became a center of economic or political power in the British colonies in North America, nor in America at large, or even in the entire United States.

Looking at it simply as one among many colonies in the New World, New England, in clear aspects, was an exceptional case. It was demographically unique (thanks to settlement by families), religiously sectarian, politically unusual, and economically attached from a European perspective. Even the phrase “Puritanical New England” can be misleading. The fishing, timber, and navigation trades—particularly in their dealings with West Indian plantations—and not religion, made life in 17th and 18th-century New England what it was. The Puritans were not necessarily admired by the inhabitants of New England nor did they represent them. At the beginning of the 17th century, in a colony in Massachusetts Bay, for example, one listener interrupted a Puritan preacher, saying:

“The affairs of New England relate to codfish, not the Lord!”

But some of the same advantages that made the Puritans strangers to that degree also allowed them to be adept at writing history. They were exceptionally skilled in culture, education, text interpretation, and institution-building. These skills distinguished them from other Americans and enabled them, in a way that distinguished them from other Americans, to tackle the challenges of dealing with what sociologist Roger Friedland called “the problem of collective representation” in the modern world. Before the rise of modern nations, the history of peoples was a science of genealogies. There is a group descended from a certain ancestor: Ibrahim or Aeneas, for example, and thus the peoples were naturally connected. But the ideal model in the modern nation represented a new problem. That the nation was supposed to be a single, shared people, sharing essential or inherited traits, rather than descending from a lineage, queen, or king.

By the end of the eighteenth century, almost no one knew how to represent this common group. But in North America, the Puritanical model was the closest. They thought of themselves and wrote about themselves not as a common group but as a chosen people, a people not sharing descent with the Lord but following the Lord. In order to meld the history of a diverse settler community into the crucible of national unity, it was not ideal by any means. But it was something they felt compelled to do.

The Puritanical influence tended to exclude many things, including the long-lasting presence of Muslims and Islam in America, and some fairness and affection in the Puritanical standards for the American experience, away from its contributions to the national history of the United States. The dominance of Puritanical institutions gave colonial New England a major role. Over the course of two centuries, customs and traditions changed greatly, but nineteenth-century historians like Francis Parkman and Henry Adams shared with their twentieth and twenty-first-century counterparts Perry Miller, Bernard Bailyn, and Jill Lepore a commitment to finding America, and the national origins of the United States, written by New England in the eighteenth century.

One of the most misleading features of Puritanical historiography was its claim that the torch of religious freedom was only a kind of commitment to Anglo-Protestantism. In reality, Puritans and Anglo-Protestants in America have always prepared and persecuted those different from them in religion: Native Americans, Catholics, Jews, Communists, and homosexual groups, Muslims, and sometimes, specifically, other Protestants. None of John Winthrop, Cotton Mather, or any other Puritanical landowners suffered actual religious persecution. The possession of power, like Anglo-Protestants in America, does not entirely conform to some of the ethical bases on which claims to moral authority in Christianity are based. Nor is it entirely consistent with the idea of America as a land of religious freedoms, as articulated by the defender of the oppressed, Thomas Paine, in 1776.

If there is any religious group that can represent the best version of religious freedom in America, it is the version of Zumurrud and Abdul Rahman. They came to America in a state of severe oppression and struggled to acknowledge their religion and freedom to practice it. Unlike Anglo-Protestants, Muslims in America objected to the tyranny of others, including Native Americans.

The most enduring result of Puritanical influence was the ongoing commitment to producing a past that focused on how the actions, usually depicted as bold and principled, of Anglo-Protestants (often beginning in New England Chesapeake) led to the establishment of the United States of America, with its government and institutions. The fact is that America’s history is not fundamentally a story of Anglo-Protestantism, as much as it is not a history of the West in a broader sense. It may not be entirely clear what it is based on, exactly, that “West.” But the most global era of history, which began with European colonization of the western part of the land, may make up a large part of it.

And if the West, partly, means the Western Hemisphere or North America, then Muslims have been part of its early communities. Conflicts over what could be an American nation and who belongs to it will continue. But the possibilities remain open for a bouquet of important answers. Historically, Muslims [in America] were Americans as much as Anglo-Protestants were Americans in turn. And in many ways, the early Muslims in America were models to be emulated in practice and honorable religious example in America. Any statement or indication to the contrary, however well-intentioned, will be driven either by deliberate chauvinism or latent chauvinism.

Sunna Files Free Newsletter - اشترك في جريدتنا المجانية

Stay updated with our latest reports, news, designs, and more by subscribing to our newsletter! Delivered straight to your inbox twice a month, our newsletter keeps you in the loop with the most important updates from our website